The Rise of SPACs

Marketing

This piece has been taken from our Q1 2021 Small Satellite Market Intelligence Report and was written by Matt Christie, our Access to Space Intern.

The Small Satellite Market Intelligence update is a quarterly report that follows the fast growing interest in small satellites with the intention to make data on the sector free and accessible.

Click here to find out more and to sign up for the reports >>

At the beginning of the space age, the development of space technology was driven by the race for technical dominance between the USA and USSR. It got off to a rapid start, sending satellites into space and humanity to the moon within 15 years. However, the post-Apollo mismatch between ambitions and resources saw public space budgets decrease due to the high cost and long timeframes associated with funding space missions. Space remained a playground for big government projects, handing out contracts to large commercial entities, with huge barriers to entry for start-up space companies. The environment for private investment in these start-up space technologies appeared akin to the vacuum in which they operated – void and no sign of life.

However, not everyone shared so bleak an outlook, with individuals and companies keeping faith in the potential of this new economic frontier. Private endeavours towards commercial spaceflight in the ‘90s, such as Kristler Aerospace, Beal Aerospace, Mircorp and the XPRIZE Foundation helped to prove the effectiveness of tactical sponsorship and shed some light on the possibilities of non-governmental space operations. These efforts resulted in a build-up of momentum for commercial opportunities within the space sector, and unlocked new avenues for investment, ushering in the New Space Era at the beginning of the 21st century. A refreshed outlook on the private investment environment in the space sector is now being recognised, with a record $8.9 billion invested in 2020, despite the COVID-19 pandemic1. Where before it was compared to the vacuum of our cosmos, it is now more aptly likened to some of the universe’s other characteristics – expanding and full of opportunities.

Today, there are more ways of raising capital than ever before. However, this does not mean that it is straightforward. With the variety of business models and commercial offerings, there is no “one size fits all” when it comes to accessing funding. New Space business leaders must take on this burden of choice when deciding the best avenue to travel in order to achieve growth sustainably From business angels to venture capitalists, corporations, or the public markets, the financing solutions are abundant.

There has been a particular increase in activity regarding space companies within the public markets as of late. The first space-focused Exchange Traded Fund (ETF), Procure Space, was launched in 2019, while the recent announcement of a new space ETF by ARK CEO Cathie Wood saw space stocks surge purely on speculation. We are now starting to see space companies take advantage of this bullish sentiment towards the industry, riding the wave of the current route to market in vogue – the Special Purpose Acquisition Company or SPAC.

What is a SPAC?

There has been a vast rise in interest over the last 2 years in what are known as Special Purpose Acquisition Companies, or SPACs. SPACs, also known as “blank check” companies, have been around for decades and were historically seen as a last resort approach to take a company public. However, due to a number of recent factors including low interest rates, volatile equity markets and an increasing number of SPAC expertise, it is becoming a more legitimate method of listing a company on the markets.

SPACs are essentially shell companies with no commercial operations and are created with the sole purpose of raising money through an Initial Public Offering (IPO) to acquire a privately held company. This is done by selling common stock, before any acquisition has taken place, meaning that investors may not have any knowledge on how their capital will be used. The capital raised is then held in a trust until either one of two things happens. Either the founders of the SPAC, also known as sponsors, identify a company of interest, which will then be taken public through acquisition using the funds raised by the SPAC’s IPO; or, if the founders fail to acquire a company within a deadline (typically two years), the SPAC is liquidated, and investors will get their money back.

SPAC mergers offer several advantages to private companies that are looking to go public compared to the traditional IPO. Should a company decide to go down the IPO route, it becomes subject to regulatory and investor scrutiny of its audited financial statements. The company must also hire an investment bank to underwrite the IPO, which can take six to nine months to complete. This involves roadshows and pitch meetings between company executives and potential investors to build up interest and demand for their shares. SPAC deals bypass this roadshow process as the capital has already been raised, prior to the merger, allowing the acquired company to go public in a much shorter time. As well as this, because the deal is technically an acquisition, securities regulators afford them a few luxuries not available to typical IPO companies. These include the ability to forecast revenues in investor pitches and publicly hype their stock, which allows SPACs to shift focus away from current business performance results. This lack of scrutiny compared to IPOs has led to some investors feeling wary towards investing in companies listed through SPACs.

Nevertheless, this has done little to affect the recent momentum, and we are now seeing a rapid increase in SPAC transactions. In 2019, there were 87 SPAC deals, with an average value of about $390 million. In 2020, there were 163, with an average of $965 million. Within the first quarter of 2021, there have been 73 SPAC transactions already, with an average value of over $2.3 billion2. When comparing 2021’s $166 billion in deals to the overall Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) deal volume, SPAC activity represents about 30% of volumes today3. This trend does not show any sign of slowing down either, with about 400 SPACs on the search for target companies.

You Can’t Spell Space Without SPAC

Traditionally the space industry has been public market shy, so why are SPACs driving New Space companies to the markets? It is straightforward to see how the acquired space companies will benefit from a SPAC deal, by enjoying the aforementioned advantages (faster route to market, less scrutiny etc.). However, the question remains as to what makes the companies of the New Space era suitable targets for a SPAC?

Space is “new” – due to their innovative nature, New Space start-up companies’ business models are often unproven, and carry a higher risk than similar sized companies in other industries. Space is competitive – companies go head-to-head with other space start-ups, billionaire space enthusiasts, and the legacy giants of the defence industry. Space is also expensive – New Space companies are capital intensive, and their burn rate is higher than almost any other industry. Paradoxically, it is these features that can make space companies an attractive candidate for a SPAC merger.

We have recently witnessed a shift in investment away from value and towards growth opportunities, with today’s investors having an unusual craving for risky bets. This allows companies with innovative and disruptive technologies, even early in their lifecycle and who are normally considered too high risk, a better chance of raising capital. Space companies are exciting, and with few publicly traded companies, they offer investors a relatively unusual investment opportunity. The accelerated route to market offered by SPACs enables these companies to strike while the iron is hot and ride on the coat tails of this market momentum.

The increasingly competitive nature of the space industry is also doing well to establish space companies as legitimate investment opportunities. Competition rewards the most optimal solution, stimulating innovation and promoting better, faster, or cheaper services. The floodgate of capital investment that a SPAC merger can open allows companies a faster track to growth, enabling them to pursue commercial options that will differentiate themselves from the rest of the competitive market.

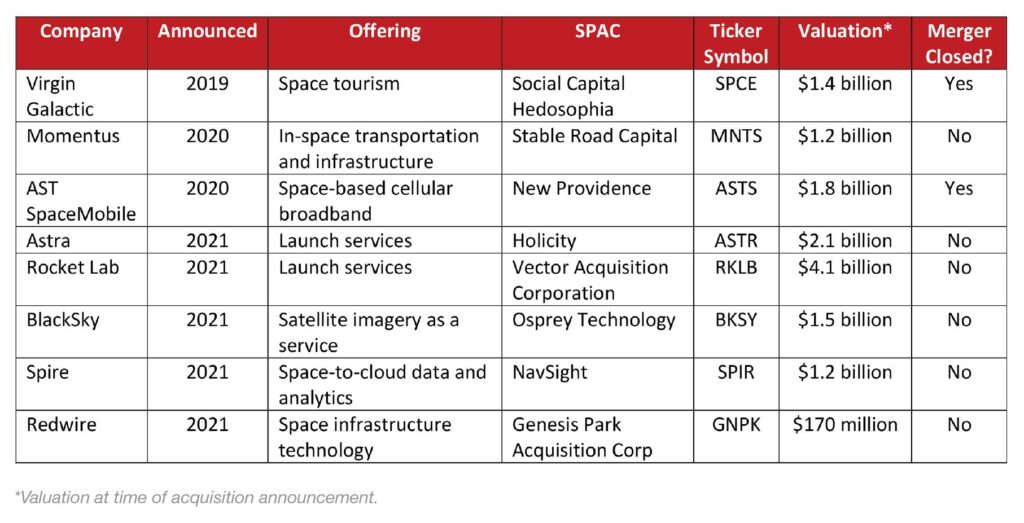

SPACs will also look to acquire target companies who have the ability to deploy the large amount of funds raised in a relatively short time period, seeking a visible and near immediate impact. This complements the capital-intensive nature of New Space companies, who can hopefully use this injection of cash to produce the returns expected. Space Companies Acquired by SPACs To date, there have been eight SPAC deals announced to bring space companies public, with a cumulative value of over $10 billion. Table 1 below displays the details of the companies within the space industry that either underwent or are undergoing a SPAC acquisition. In addition to the companies below, it was announced in March of this year that Virgin Orbit is also searching for a SPAC to merge with.

Despite the apparent benefits of SPACs in terms of offering a “simple” route to market, not all of these deals have gone as smoothly as initially hoped. Space companies operate in a highly regulated environment, and while many regulated companies find success in the public markets, the process can take time and experience more turbulence than desired.

Following their announcement of intentions to become a publicly traded company via SPAC in 2020, the Momentus CEO and founder resigned in early 2021 after an investigation into his access to restricted space technology interfered with the attempt to go public. The resignation came in response to US government national security and foreign ownership concerns surrounding the company.

Issues with government contracts may also upset the process for potential SPAC target companies. Some of the government contracting programs are not readily adaptable to the company going public in a short time period. Companies who work with classified or sensitive technologies will have to be re-vetted by the government before they can go public, while some contracts are awarded under small company qualification programmes that may not be appropriate when a company becomes publicly traded.

As well as this, there have been concerns about valuations. Rocket Lab has a $4.1 billion valuation, at 5.4 times the 2025 expected revenue of $749 million. Spire has a $1.2 billion valuation, at 5.4 times their 2023 expected revenue of $227 million, and AST SpaceMobile has a $1.8 billion valuation at 1.8 times their 2024 expected EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization) of $1 billion5. The revenues that the companies will have to generate to meet these valuations have prompted some comments of a potential bubble, as well as the danger of damaging shareholder value if milestones are missed.

It is too early to predict the success of these SPACs and any others that may follow. Achieving a public listing is not the finish line, and the companies will have to take key steps to realize the levels of growth expected, in a sustainable way. Some of these will fail to reach metaphorical (or sometimes literal) orbit, while others will go interstellar. Such is the nature of the markets. However, what is clear is that investors are hungry for new and exciting opportunities to make returns on their investments. As long as there is an appetite, there will be no shortage of companies attempting to satiate it.

Will an explosion in public market interest, along with the continued declining launch costs and advances in technology, unlock the widely touted trillion-dollar space industry? Or is this the beginning of a dot-com-like bubble? Either way, it feels like the start of a defining period for New Space, and when the dust settles, the new titans of the space industry will be revealed.